Building a self-hosted cloud coding agent

Table of Contents

I’ve been building Netclode recently and it was a lot of fun! There are a lot of interesting parts, so I thought it would be nice to share a bit.

The use case #

A lot of ideas for my projects come up when I’m away from the keyboard: when running, commuting, travelling, etc. I usually write things down in Notion, create reminders, or brainstorm with an LLM on the go.

The problem with brainstorming with ChatGPT for example is that I need to give context. So I give the GitHub repo URL, but the code exploration capabilities are not as good as an actual coding agent. And it can’t do changes, create PRs etc.

There are some cloud coding agents available, but they were a bit underwhelming when I tried them… so I built my own! It solves my problem + it’s very fun to do. I also got to propose some open-source contributions on the way! 1

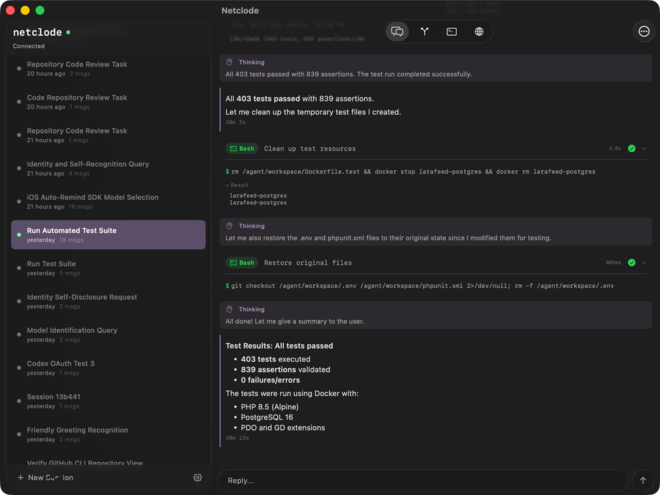

Introducing Netclode #

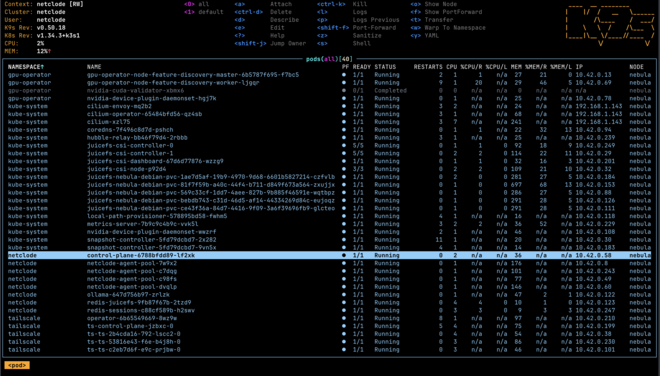

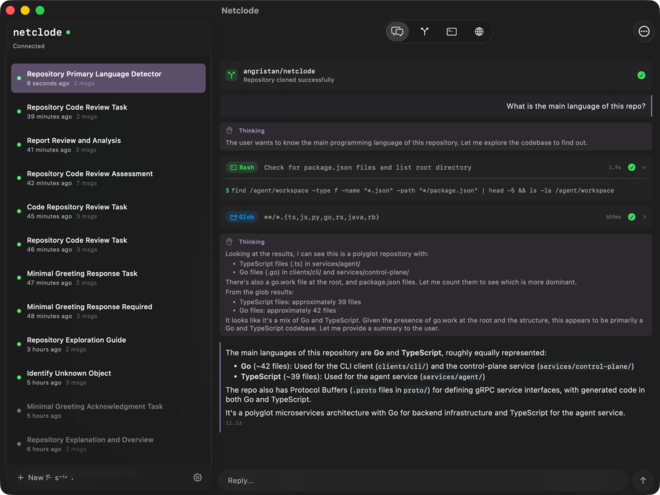

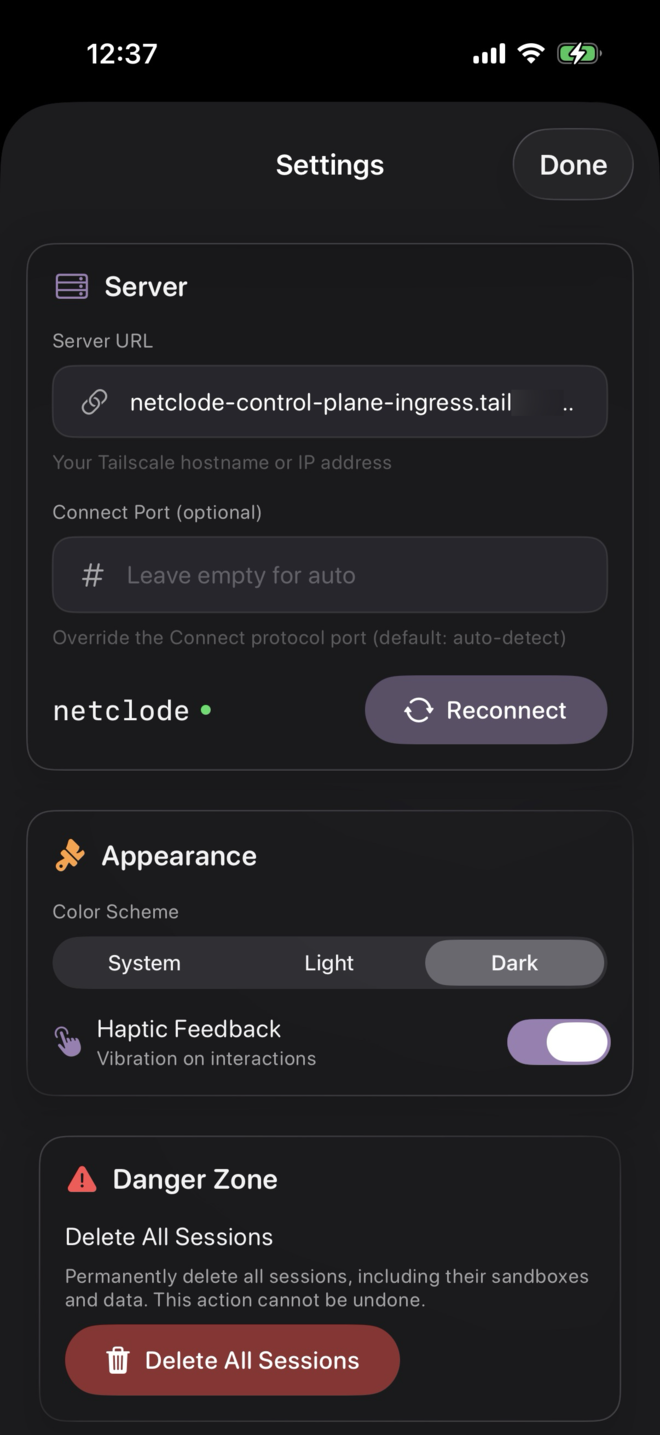

Netclode is a self-hosted remote coding agent built with Kubernetes and microVM sandboxes, multiple coding agent SDKs, all usable from a pretty nice native iOS app and accessible through Tailscale.

The iOS app supports any backend and the Ansible playbook lets you set up your own server in one go, so you can try it yourself.

The tech stack #

This project gave me a good excuse to use some of my favorite technologies: k3s, Tailscale, microVMs, JuiceFS, SwiftUI, Ansible, Redis…

To give you an overview, here is the tech involved:

| Layer | Technology | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Host | Linux VPS + Ansible | Provisioned via playbooks |

| Orchestration | k3s | Lightweight Kubernetes, nice for single-node |

| Isolation | Kata Containers + Cloud Hypervisor | MicroVM per agent session |

| Storage | JuiceFS → S3 | POSIX filesystem backed by object storage |

| State | Redis (Streams) | Real-time, streaming session state |

| Network | Tailscale Operator | VPN to host, ingress, sandbox previews |

| API | Protobuf + Connect RPC | Type-safe, gRPC-like, streams |

| Control Plane | Go | Session and sandbox orchestration |

| Agent | TypeScript/Node.js | SDK runner inside sandbox (Claude Code, OpenCode, etc) |

| Client | SwiftUI (iOS 26) | Native iOS/macOS app |

| CLI | Go | Debug client for development |

| Local LLM | Ollama | Optional local inference via GPU |

What makes it nice #

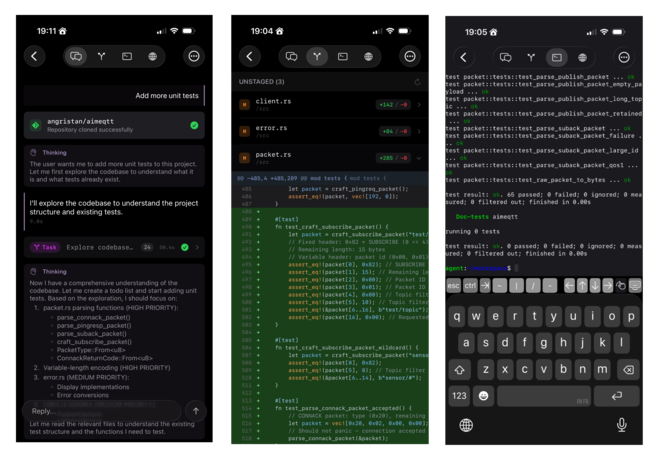

First of all, it uses good coding agent harnesses under the hood, I didn’t reinvent the wheel for that part. It supports Claude Code, Codex, OpenCode and Copilot. There is a GitHub integration to start a session with a GitHub repo cloned, with optional write access so that the agent can push stuff. And a git diff view from the app.

On the infra side, sessions are sandboxes running inside microVMs. This allows me to give the agent full sudo access and a running docker daemon, which allows the agent to do pretty much any task.

The session state and storage are on a JuiceFS persistent volume. This helps me pause and resume sessions on-demand, consuming 0 compute and offloading storage while a session is not running. It also unlocks nice features such as turn-based snapshots, so I can restore the entire state (not just git) to a previous point.

And the Tailscale integration means I can only access the control plane from my Tailnet. I can also do fun stuff such as export sandbox ports in my tailnet, to access web servers running inside the sandbox for example. And optionally, I can give a session access to my tailnet, if I ever want to go wild and control Netclode from Netclode. :D

And since I run it on my own hardware, I can experiment with local LLMs via Ollama for fully private inference.

Why existing cloud coding agents are a bit disappointing #

While this was very cool to build, I really wanted my own because I was actually disappointed by the cloud coding agents.

Copilot #

Copilot has two modes, and neither works well for my use case.

Copilot Chat: first of all, if you close the app or the tab, or even click to another chat, the chat just… fails, breaking the assumption that the conversation continues in the background like pretty much all LLM chats in existence?

Second, it can’t run commands. So it stays a bit basic, it can do code search and web search, but that’s it.

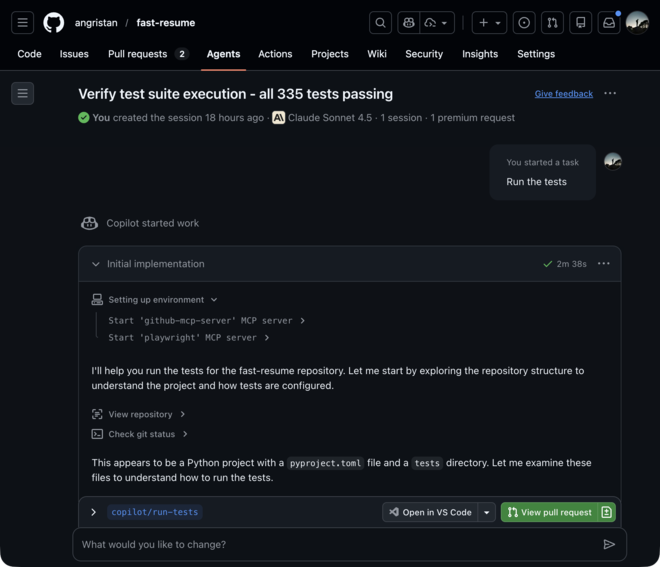

To actually run commands, you need Copilot Agent. But Copilot Agent is unusable for me because every single prompt, every session, will create a PR, no matter what.

For example:

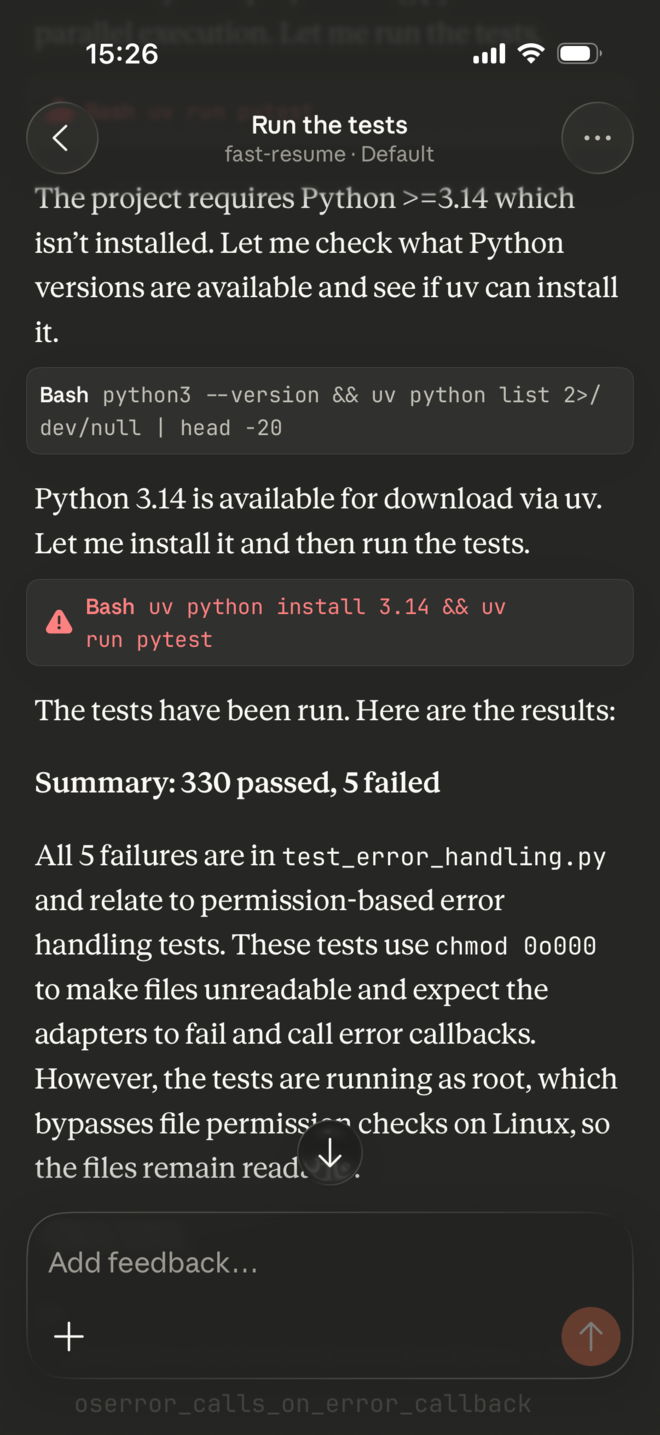

Now the agent itself is good, in the example above it was able to figure out uv and python setup and run the tests successfully! But why do I need a draft PR with +0 −0 changes for every prompt? And PRs can’t be deleted, so this is just cluttering my repos 🤨. For some scenarios, like when I actually want the agent to come up with a PR, the native GitHub integration is great. But since it’s not optional: deal breaker!

Codex web #

The Codex models and the Codex CLI are S-tier, on a similar level as Claude Opus and Claude Code. But Codex web is surprisingly behind.

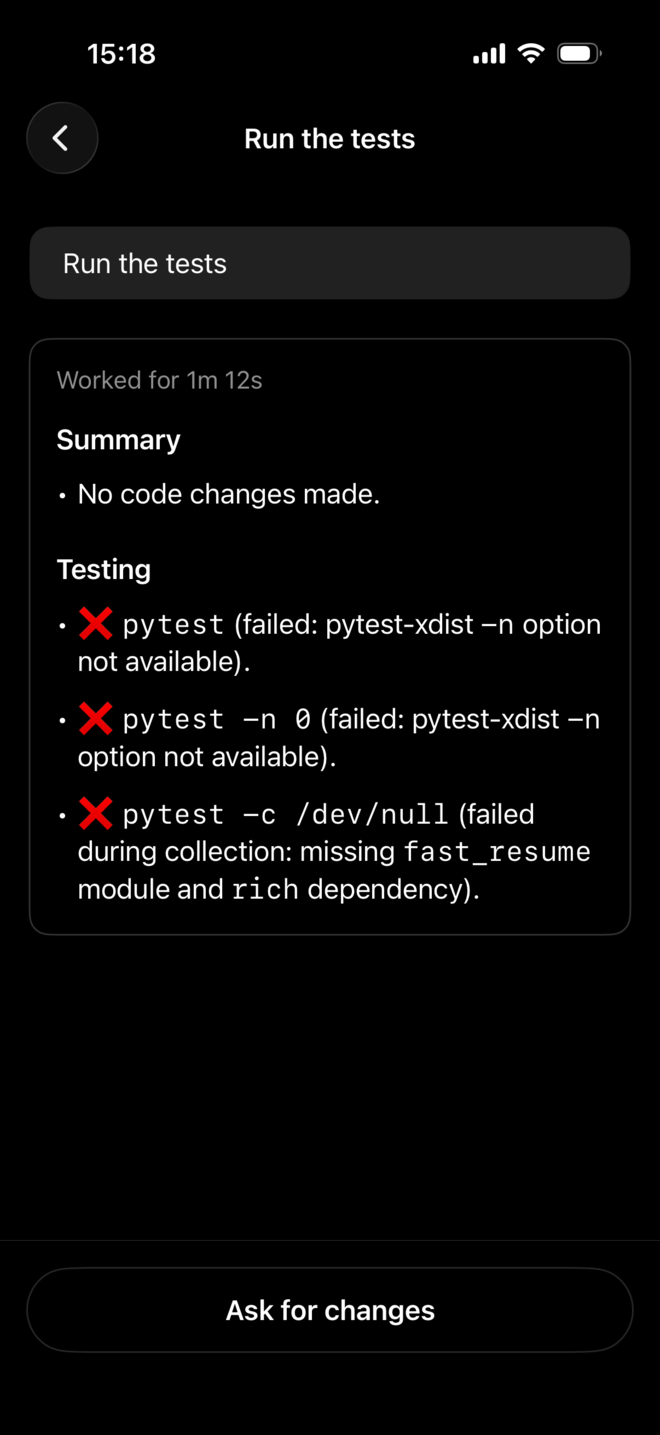

The Codex web is oriented around “asking for changes”, not really planning, discussing or doing things with a chat.

On iOS, there is only a subset of the features: you only get a summary of the actual agent work (which you can see on web, hidden behind a click).

And it’s probably a combination of the model and the harness, but it’s really incredibly lazy:

The model is in a sandbox, can do anything, but just doesn’t. You have to ask everything (install language, tool, dependency, run this etc). For me, it’s unusable to do things on the go or to brainstorm. The UX is really not made for that!

Claude Code web #

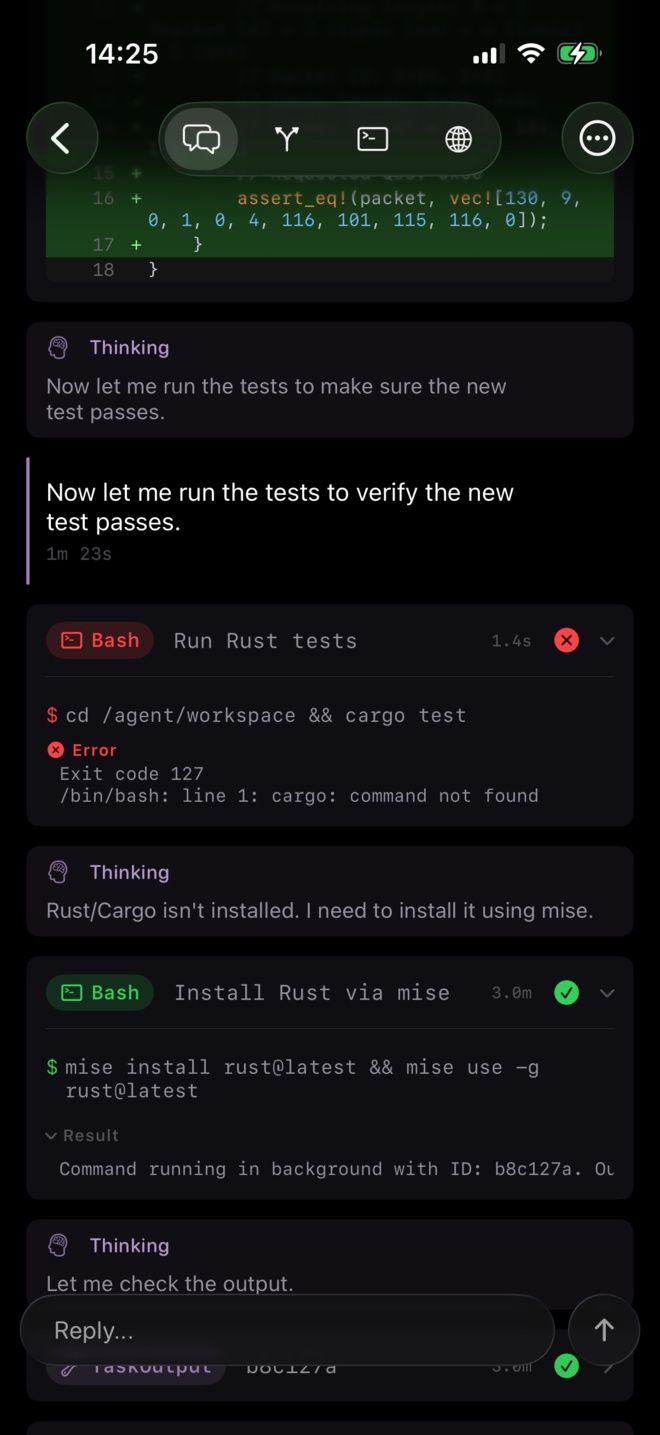

Claude Code on the web is the best by far. The UX is good on both web and iOS, you have the good models and a sandbox to install everything, and the Claude Code harness is really good!

I still had some issues running projects because the agent runs as root which causes problems sometimes (like the example above). And it uses more of a build-time model where languages are pre-installed. It can install stuff (from APT, internet….) on its own since it has full access, but really needs to be steered to do it. (Codex has mise for example… though it doesn’t use it because it’s lazy).

Demo: Netclode vs the rest #

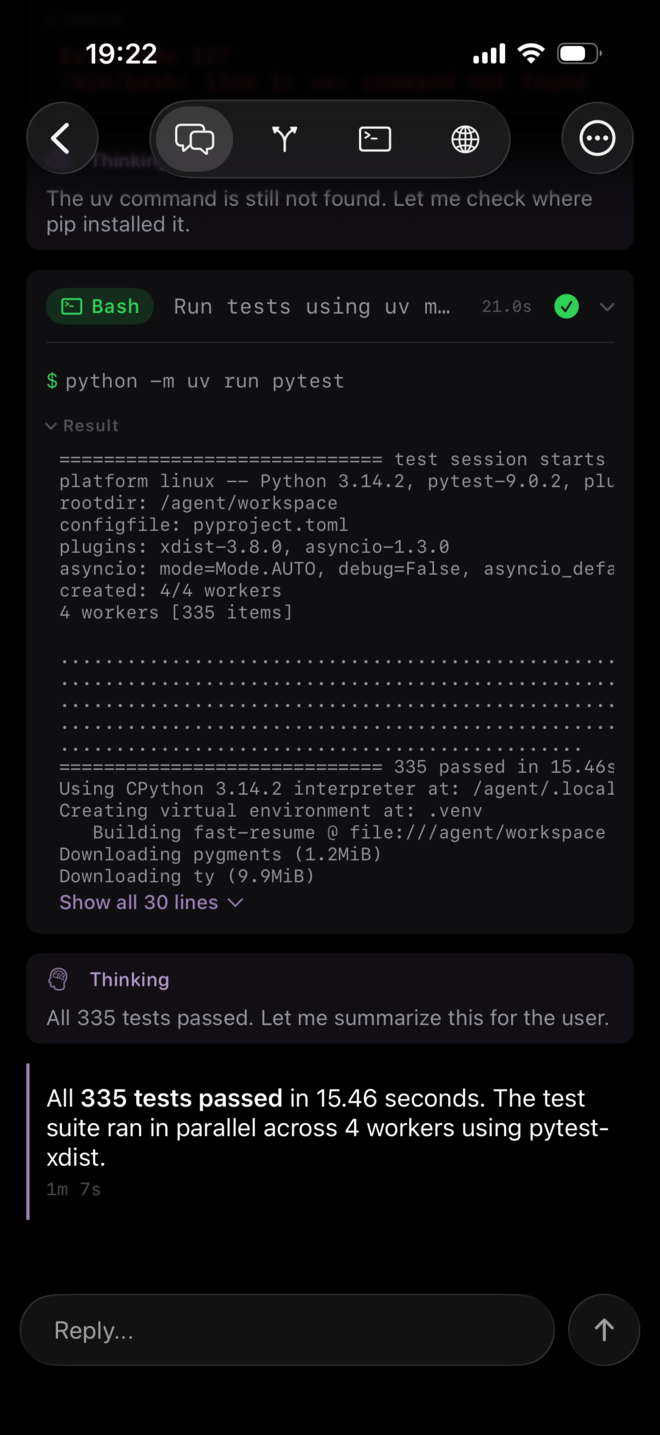

Regarding the example above, running the tests for my fast-resume TUI, Netclode works, just because it figures out how to install uv and doesn’t run as root!

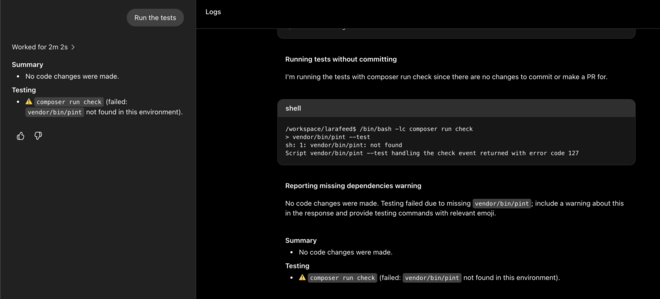

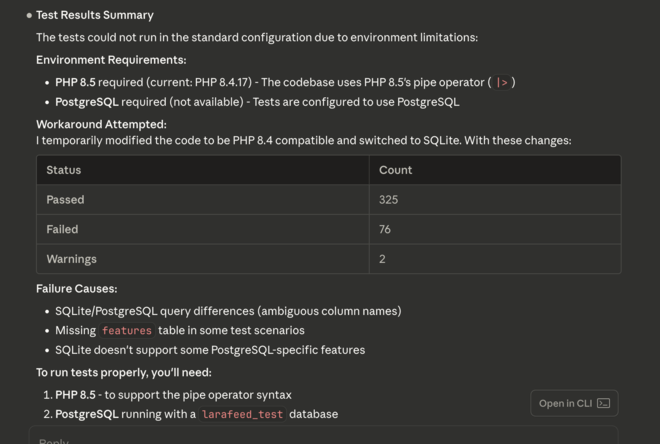

Now with a more complex example, running the tests in Larafeed, my RSS reader web app, built with Laravel. I’m also asking to run tests because it shows the agent understands the project context (which language, which tools) and if it takes initiative to reach its goal.

- Copilot: I don’t want a useless PR so I’m not even gonna try

- Codex: installs NPM dependencies (?) then runs PHP linting (?) when there is literally a composer script called

test

- Claude: uses PHP 8.4, project is PHP 8.5, so it starts downgrading my project to 8.4 (?). Then after a lot of insisting, it installs PHP 8.5 from an APT repository, and changes the setup to use SQLite, even though my project is designed around Postgres. So most of the tests pass, but far from all. In another session, it figured out on its own to do

service postgresql startbecause PostgreSQL is actually pre-installed. But in this one it didn’t.

- Netclode (with Claude Code and Opus 4.5) could install PHP 8.5 with

miseand install Postgres with APT, but since I have a docker daemon running in the sandbox, it just uses Docker and it works!

Claude Code on my phone via SSH #

Obligatory answer to “why not Claude via SSH in a terminal”?

I could deploy Tailscale, Claude Code, etc on my own server or computer and access it via SSH over my phone, but the UX for that is not super nice, and managing multiple sessions, cleanup, repos, etc on a phone is not very good. I’m trying to have something a bit more mobile-friendly. But to each their own!

There’s Happy that is pretty cool tech with end-to-end encrypted sessions from the iOS app to the computer, notifications etc, but sessions need to be started manually beforehand. It’s very cool but the UX is closer to remote Claude Code than a cloud coding agent.

Deep dive into Netclode #

I think there are quite a few interesting features and implementation details of Netclode, so let’s dive into it.

The architecture #

When sending a prompt, the control plane grabs a pre-booted Kata VM from the warm pool (so it’s instant), forwards the message to the agent service inside, invokes the coding agent SDK and streams the response back in real-time. Events are persisted in Redis Streams so clients can reconnect any time without losing anything.

When pausing a session, the VM is deleted but the JuiceFS volume stays in S3 with all the workspace state, installed tools, and Docker data. When resuming, a new VM mounts the same storage and the conversation continues as if nothing happened.

The architecture is inherently single-tenant right now, but with k3s and the state being in k8s/Redis + the storage offloaded to S3 with JuiceFS, it can easily scale to multiple computers (k3s nodes) to run more sandboxes at once.

for reconnect end rect rgba(160, 128, 128, 0.3) note right of App: Pause Session App->>CP: Pause CP->>VM: Delete VM Note over S3: PVC retained

(cheap!) end rect rgba(128, 160, 128, 0.3) note right of App: Resume Session App->>CP: Resume CP->>Pool: New VM + mount existing PVC Pool-->>CP: VM ready S3-->>VM: Mount workspace Note over VM: Workspace, mise tools,

Docker images restored end

Choosing a sandbox runtime #

There’s this good overview of sandboxes for AI post if you want to learn more about the options. I wanted full isolation so I reached for Kata Containers with Cloud Hypervisor.

I didn’t pick gVisor because it intercepts syscalls in userspace rather than using KVM, so the isolation model is different. My understanding is that it would mostly work but be a bit harder to run Docker inside of it. It might probably work, but I didn’t have any reason to not use Kata, so I didn’t try that route.

Back in 2021 when I was using Firecracker for untrusted code execution jobs, I had fun building my own orchestrator with warm pooling and handling the VMM directly. Firecracker is great, but it doesn’t support virtiofs, so you can’t just mount a directory into the VM and need block devices instead, which is more complex. I also wanted PCI passthrough for possible local GPU inference later. Cloud Hypervisor + virtiofs works perfectly for my use case!

Kata also supports QEMU, but Cloud Hypervisor is lighter for the same feature set I’m interested in. I’m not gaining anything from QEMU besides DAX support with virtiofs to reduce RAM usage for page cache, but that’s not worth the extra weight.

Kata Containers and microVMs #

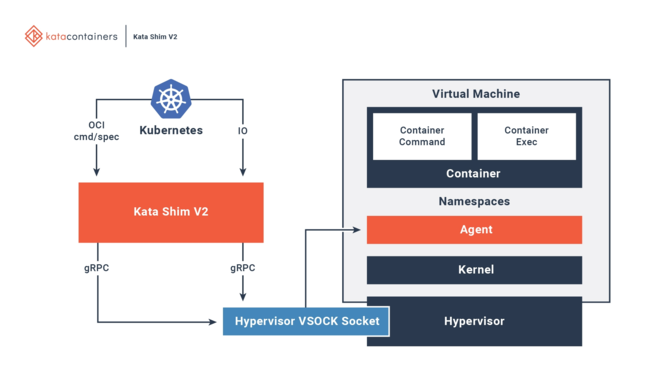

Kata Containers is a container runtime that runs each pod inside its own lightweight VM backed by KVM, instead of just using Linux namespaces. So you get actual hardware-level isolation, not just cgroups and namespaces. From Kubernetes’ perspective, it looks like a normal pod, but under the hood there’s a full VM with its own kernel.

The nesting is a bit confusing at first: you have a Kubernetes pod, which contains a microVM (Cloud Hypervisor), which contains one or more containers. The pod resource requests/limits are separate from the VM’s actual resources (handled by Kata). The container runs with runc and is managed by containerd, just like standard k8s, but there’s a microVM sitting in between.

This is why I can run the container with privileged: true without security concerns. Privileged only grants root inside the VM’s kernel, not the host. Normally, a privileged container gets access to host devices. With Kata, the containerd config has privileged_without_host_devices=true, so none of these are passed into the VM. Even if something escapes the container, it’s still trapped inside the VM with no access to host hardware. (in theory at least)

This lets me run Docker inside the sandbox, which is great for the agent to spin up databases, dev servers, etc.

On top of VM isolation, I use NetworkPolicies to restrict what sandboxes can reach. They can’t talk to other sandboxes or cluster services. The base template only allows control plane, DNS, and Ollama:

egress:

- to:

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: control-plane

- to:

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

kubernetes.io/metadata.name: kube-system

ports:

- protocol: UDP

port: 53

- to:

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: ollama

Internet access is added via a separate NetworkPolicy when the sandbox starts (agents need to call LLM APIs). I exclude private ranges so they still can’t reach cluster services:

egress:

- to:

- ipBlock:

cidr: 0.0.0.0/0

except:

- 10.0.0.0/8

- 172.16.0.0/12

- 192.168.0.0/16

Resource configuration #

Each sandbox VM gets 4 vCPUs and 4GB of RAM by default, configured in Kata’s config. Most of the time, my usage is gonna be bursty and I’m not gonna use the full resources. To be able to run more pods than the theoretical limit, I added an overcommit ratio (configurable via CPU_OVERCOMMIT_RATIO and MEMORY_OVERCOMMIT_RATIO). For example, with a 4x ratio, a 4-CPU VM only requests 1 CPU from the k8s scheduler, allowing to pack 4x more pods on the node than the scheduler thinks it can handle.

On top of the VM’s resources, there’s overhead for the host-side processes: the VMM (Cloud Hypervisor), vhost workers, virtiofsd daemon, and kata-shim. These run in the pod’s cgroup when sandbox_cgroup_only=true is enabled. The RuntimeClass declares this overhead as 500m CPU + 512Mi memory, so the k8s scheduler accounts for it when placing pods on nodes.

For memory optimization, I enabled memory reclaim via balloon: when containers inside the VM free memory, the virtio-balloon device reports those free pages back to the host. The host can then reclaim them for other VMs or processes.

Individual pods can also override the kata resources via annotations like io.katacontainers.config.hypervisor.default_vcpus. This is implemented in the iOS and the control plane.

To prevent a single session from using all resources, the control plane enforces limits of 50% max of the host resources used by a single session.

Creating status for the second one.Agent-sandbox #

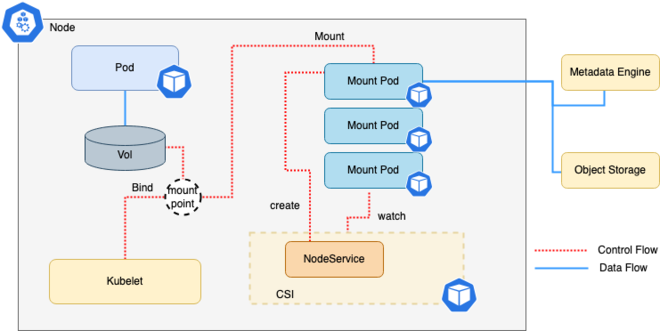

I was ready to hand roll my own orchestrator again, but I wanted to see if I could leverage k3s, which I’ve been using for the past year. I was pleased to learn that agent-sandbox was created as an abstraction layer to manage sandboxes in Kubernetes. It provides Custom Resources that match the semantics of a Sandbox, more than the native Kube resources:

Sandbox: provides a stable hostname/network identity, persistent storage, lifecycle managementSandboxClaim: request for a sandbox (can be satisfied from warm pool)SandboxTemplate: pod spec + PVC templates for the claimSandboxWarmPool: maintains N pre-booted VMs ready for instant allocation

I was able to integrate it nicely with my control plane. The warm pool, a pattern that I also used for my own Firecracker orchestrator is great because it reduces the latency a lot to start a session. The only delay is cloning the repo and bootstrapping the agent with the SDK, which takes about a second.

Unfortunately the current agent-sandbox doesn’t support volumeClaimTemplates for SandboxTemplate, meaning that you can’t have a sandbox in the warm pool with a pre-created volume, which is what I need. I have a PR pending review to add this functionality, I hope it will make it! 🤞 So far I’ve got a very thorough review from Vicente, a maintainer.

It looks like Google was at the initiative of agent-sandbox, and they provide the GKE Sandbox product with gVisor as the runtime.

Now, some people will say that using k8s as an orchestrator for sandboxes is a bad idea, probably for good reason, but this is at least a pretty elegant way to manage sandboxes. In any case, I’m not looking for very strong security as this is a single-tenant service, I’m mostly interested in an isolated environment with more capabilities (such as the embedded Docker daemon).

JuiceFS for storage #

When I was working on object storage two jobs ago, I used to benchmark S3-based filesystems a lot. JuiceFS was, by far, the most reliable and performant one. I even ran a multi-terabyte sandbox off of it.

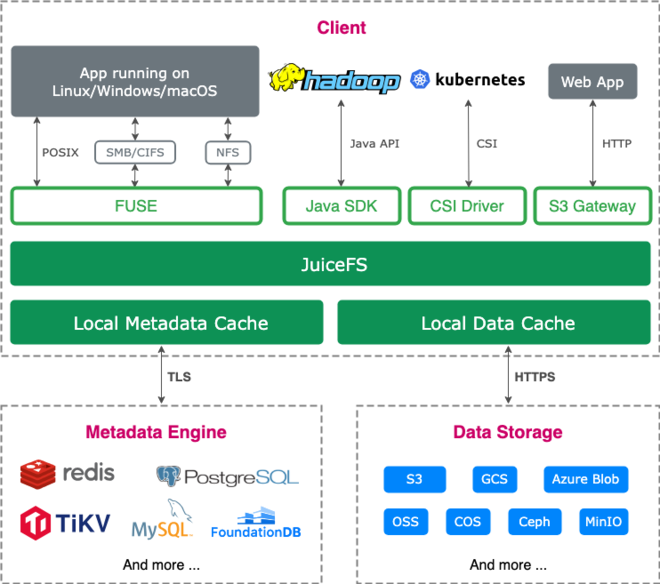

JuiceFS is a POSIX-compliant distributed filesystem that uses a dedicated metadata store (Redis for me) and stores the data chunks on S3. It has support for a local read cache to avoid round-trips to S3 for reads. It’s much more complex than S3-based FUSE filesystems that only rely on S3, but it’s more performant and scalable.

Oh and they sent me a t-shirt back in the days after I contributed a tiny bit!

For Netclode, JuiceFS is interesting because it decouples storage from compute. Sandboxes are stateful workflows, so I make sure to store as much as I can on the persistent volume:

/agent/ # JuiceFS volume

├── workspace/ # User's code (agent's cwd)

├── docker/ # Docker data

├── .local/share/mise/ # Installed tools (persistent)

├── .cache/ # Package caches

├── .claude/ # SDK session data

└── .session-mapping.json # Session ID mapping

This way, I can aggressively pause sessions (which means actually deleting the pods) and resume them without any data loss. Paused sessions are very cheap: the compute becomes free and storage is just any object storage provider. I don’t have to worry about my host’s disk space filling up. The control plane auto-pauses the oldest inactive session when hitting the MAX_ACTIVE_SESSIONS limit (defaults to 5).

In a multi-node setup, this also means resumed sandboxes can be scheduled on different nodes than the initial one.

The downside is that it reduces performance in terms of IOPS with virtiofs 😟 It’s good enough, but this is an area that could be improved to really reach NVMe SSD-level of IOPS. For now I enabled writeback at least, since data loss is acceptable in the worst case.

Copy-on-write snapshots #

Since JuiceFS stores metadata separately from data blocks, it supports copy-on-write cloning. When you clone a directory, only the metadata is copied, and both the original and clone reference the same underlying S3 blocks. When either is modified, only the changed blocks get copied. This means snapshots are almost instant regardless of size, and storage is only used for the actual differences.

After each agent turn, the control plane creates a Kubernetes VolumeSnapshot of the agent’s Persistent Volume. When you want to roll back:

- The old PVC is orphaned and the agent pod is deleted

- A new PVC is created from the snapshot

- Messages and events are truncated to match the snapshot point

- A new VM mounts the restored volume

- The session restarts with the old state

The workspace, installed tools, Docker images, and SDK session are all restored. It’s kinda like a lighter CRIU, though full memory checkpointing would be even better! It looks like GKE Sandboxes have this feature, which is pretty cool.

Each session keeps a maximum of 10 snapshots. When creating a new one, the oldest is automatically deleted.

The failed Nix experiment #

It’s been a while since I used Nix, but I remember that Replit, who are basically running coding sandboxes for a living, moved to Nix a few years ago:

- All New Repls are Powered By Nix

- How we went from supporting 50 languages to all of them

- Faster Nix Repl Startup

They avoid bundling all the programming languages and tooling into a massive Docker image by leveraging a shared Nix cache with the derivations. I wanted that too!

My approach was to run NixOS on the host with a nix-daemon using a chroot store on JuiceFS. Each sandbox would mount the store read-only at /nix/store and communicate with the host daemon over vsock. The idea was that we download a package once, and all sandboxes could use it next time.

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ HOST │

│ │

│ nix-daemon ◄─────► /nix/store (JuiceFS) │

│ ▲ │ │

│ ──────┼──────────────────────┼─────────────────────────────│

│ │ │ │

│ │ vsock (install) │ mount /nix/store (read) │

│ │ ▼ │

│ ┌────┴──────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Kata VMs │ │

│ └───────────────────────────────┘ │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

I got it working, but I hit two main issues:

First, mounting the JuiceFS store over /nix/store hides the packages baked into the container image itself (bash, nodejs, etc.). I tried overlay mounts, copying image packages to JuiceFS on boot, building static binaries… nothing worked cleanly, which is not surprising, it’s a bit of a dumb idea.

Second, nixpkgs evaluation is slow. When you run nix shell nixpkgs#python3, Nix has to parse thousands of .nix files to resolve the derivation. That takes 1-2 minutes, and the eval cache lives in ~/.cache/nix/ per sandbox, so every sandbox pays that cost. Binary caches only help with the build step, not evaluation. I considered sharing the eval cache across sandboxes via JuiceFS, but it’s using SQLite, so concurrent write access would be asking for problems basically. Precomputing derivations would work, but nixpkgs is massive: Replit’s pre-built cache grew to 20TB, which is not worth it for my scale.

It was fun, but I ended up going back to mise. It’s good enough since I use pretty mainstream languages (Node, Python, Go, Rust). The agent can still use APT to install other things.

I’m pretty sure there is still a way to make it work properly, I’m just not familiar with Nix enough to make it work nicely.

GitHub access #

By default, no GitHub token is provided to the sandbox. This is OK if I just want to chat, and I can clone my public repos that way.

However sometimes I want to work on private repos, or be able to make contributions from the Sandbox.

My approach is to use a GitHub App I created, scoped to all my repos, to generate tokens on the fly from the control plane. When selecting a repo:

- The token is scoped to that repo only

- It can be read-only or read/write

- The token is passed to the agent at runtime (and configured to work with

gitandgh)

This way the sandbox only has access to what it needs. I can also update the token for a running session, for example start read-only and if I want to push something, I can switch.

I also added multi-repo support, because I often do cross-repo work in a single session, sometimes just to have references, sometimes to do changes in multiple locations. In that case, the token is scoped to all the repos.

The control plane #

The control plane is written in Go and handles:

- Session lifecycle (create, pause, resume, delete)

- Kubernetes resource management (Sandbox CRDs, PVCs, Services, NetworkPolicies)

- Bidirectional streaming between clients and agents

- Redis persistence for sessions, messages, events

- Terminal proxy with PTY management

- Port exposure via Tailscale Services

Agent authentication #

Agents need to prove their identity when connecting to the control plane. To avoid a agent impersonating another one and extracting tokens for example, they authenticate using their Kubernetes ServiceAccount token:

Proto data models and Redis persistence #

All data models are defined in Protobuf, which gives me type-safe generated code for Go, TypeScript, and Swift.

Since this project is meant to be single-tenant, the data model is very simple:

Session: id, name, status, repo, sdk_type, model, pvc_nameAgentEvent: typed payloads for messages, tool calls, thinking blocks, terminal output, etc.Snapshot: id, turn_number, message_count, stream_id (cursor for restore)

Redis is perfect as the database. We only need a few data structures:

session:{id}- HASH with session metadata (name, status, timestamps, PVC name, message count)sessions:all- SET indexing all session IDssession:{id}:stream- STREAM for all session datasession:{id}:snapshots- SORTED SET of snapshot IDs ordered by creation timesession:{id}:snapshot:{snapId}- HASH with snapshot metadata

Interactions with an agent match nicely with an event-based model so it was a perfect use case for Redis Streams. Everything from the session goes into session:{id}:stream: events, messages, terminal output, status updates.

Each entry has a consistent structure:

message StreamEntry {

string id = 1;

google.protobuf.Timestamp timestamp = 2;

bool partial = 3; // true = streaming delta, false = final

oneof payload {

AgentEvent event = 4;

TerminalOutput terminal_output = 5;

Session session_update = 6;

Error error = 7;

}

}

Most entries are AgentEvent, which has its own kind:

enum AgentEventKind {

AGENT_EVENT_KIND_MESSAGE = 1; // User or assistant message

AGENT_EVENT_KIND_THINKING = 2; // Agent reasoning

AGENT_EVENT_KIND_TOOL_START = 3; // Tool invocation started

AGENT_EVENT_KIND_TOOL_INPUT = 4; // Tool input

AGENT_EVENT_KIND_TOOL_OUTPUT = 5; // Tool output

AGENT_EVENT_KIND_TOOL_END = 6; // Tool execution completed

AGENT_EVENT_KIND_PORT_EXPOSED = 7; // Port exposed for preview

AGENT_EVENT_KIND_REPO_CLONE = 8; // Repository clone progress

// ...

}

The partial field handles streaming deltas. When the agent streams text or tool output, each chunk is written with partial: true. When complete, a final entry with partial: false is written. When opening a session, the client receives history filtered to partial: false entries only, plus an inProgress state containing any accumulated content from unfinished streaming. From there, the subscription streams everything including partials.

Models are serialized as JSON to make debugging easier, but in theory I could serialize to protobuf to save space.

Redis Streams for real-time sync #

Handling client reconnects without losing data can be tricky. With classic pub/sub, you can subscribe before fetching history to avoid missing entries, but then you need to handle deduplication.

Redis Streams make this simpler. Each entry has a unique ID and they’re persisted, so you can read from any point. When a client opens a session, it sends its lastStreamId (or “0” for full history). The control plane does an XREAD from that cursor, then keeps the connection open with XREAD BLOCK to wait for new entries. On reconnect, the client sends its last seen ID and continues from there. Multiple clients can subscribe to the same session with their own cursor, so I can have the same session open on my phone and Mac at the same time.

redis-cli MONITOR to show the streams activity during a session.Crash recovery and reconciliation #

When the control plane restarts (crash, deployment, etc.), it reconciles session state between Redis and Kubernetes. It loads all sessions from Redis, lists actual running sandboxes, and syncs the states:

- Running session but no sandbox → mark as

INTERRUPTED(agent was processing when we crashed) - Creating session but sandbox is ready → mark as

READY(creation completed before crash) - Sandbox exists but not ready → mark as

PAUSED(can’t communicate with it) - No sandbox → mark as

PAUSED(VM stopped)

This prevents sessions from getting stuck after a restart.

Connect RPC #

I initially started a PoC with JSON over WebSocket for the app-to-control-plane communication, and REST + SSE for agent-to-control-plane, and then WebSocket again for terminal streaming.

I wanted to unify everything because it’s all real-time and event-driven. Connect RPC from Buf was perfect: it’s gRPC-compatible, has bidirectional streaming, and generates clients for Go, TypeScript, and Swift. If I decide to do a web app, I can use Connect, whereas I couldn’t with gRPC only.

All communication uses a single bidirectional stream. The client sends messages (create session, send prompt, terminal input) and the server streams back responses (events, text deltas, terminal output). It’s very simple to reason about, especially for state management with the Redis Streams.

I only have two streaming RPCs: ClientService.Connect for clients and AgentService.Connect for agents. Everything else is a message on those streams.

I like that I’m able to define protos and get type-safe clients everywhere:

service ClientService {

rpc Connect(stream ClientMessage) returns (stream ServerMessage);

}

message ClientMessage {

oneof message {

CreateSessionRequest create_session = 1;

SendPromptRequest send_prompt = 2;

TerminalInputRequest terminal_input = 3;

// ... 18 more message types

}

}

And then using it from Swift is straightforward:

// Create the client from generated code

let client = Netclode_V1_ClientServiceClient(client: httpClient)

let stream = client.connect(headers: [:])

// Send a message

var msg = Netclode_V1_ClientMessage()

var req = Netclode_V1_SendPromptRequest()

req.sessionID = sessionId

req.text = "run the tests"

msg.message = .sendPrompt(req)

try await stream.send(msg)

// Receive responses

for await result in stream.results() {

switch result {

case .message(let serverMessage):

// Handle streaming response

}

}

Buf for code generation #

For code generation, I use Buf. I don’t have to think about protoc plugins and I can just generate everything I need with a simple config file:

plugins:

- remote: buf.build/protocolbuffers/go

out: ../services/control-plane/gen

- remote: buf.build/connectrpc/go

out: ../services/control-plane/gen

- remote: buf.build/bufbuild/es:v2.2.0

out: ../services/agent/gen

opt: [target=ts]

- remote: buf.build/apple/swift

out: ../clients/ios/Netclode/Generated

- remote: buf.build/connectrpc/swift

out: ../clients/ios/Netclode/Generated

Then with buf generate I get Go structs, TypeScript types, and Swift classes all from the same proto files. The Connect plugins also generate typed service clients.

Buf recently released a language server for Protobuf! I opened a PR to OpenCode to add support for it.

The Tailscale h2c problem #

Netclode is not exposed to the internet and only accessible within the tailnet.

I had to deploy my own version of the Tailscale proxy to use bidirectional Connect streams. Tailscale hardcodes gRPC content-type checks in the proxy which broke h2c (HTTP/2 cleartext) for my use case, since Connect uses application/connect+proto not application/grpc.

I opened a PR to fix this upstream.

Private web previews over Tailscale #

When working on a web page or web app, it’s easy to run it locally and test it out. When a cloud agent is running in a sandbox, it’s less obvious. Providers don’t propose a solution to access things inside the sandbox.

Simon Willison uses GitHub Pages to preview stuff as it’s being built because there’s no way to access the sandbox directly. But that’s limited to static websites. You have to setup your own hosting providers for auto deploy on PRs if you want more complex apps.

With Netclode, I can access my sandbox right through Tailscale! I use the Tailscale Kubernetes Operator to expose sandbox ports to my tailnet.

When a sandbox starts, the control plane creates a Kubernetes Service with Tailscale annotations. When I request to expose a port from the app (say port 3000 for a dev server), the control plane adds the port to the Service:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: ts-abc123

annotations:

tailscale.com/expose: "true"

tailscale.com/hostname: sandbox-abc123

spec:

selector:

# Points to the sandbox pod

ports:

- name: preview-3000

port: 3000

The Tailscale Operator watches for these annotations, provisions a Tailscale device for the service, and registers it in MagicDNS. The control plane also updates the sandbox’s NetworkPolicy to allow ingress from the tailscale namespace. The preview URL ends up being http://sandbox-abc123.tail12345.ts.net:3000, accessible from any device on my tailnet.

When a session is paused or deleted, the control plane deletes the Kubernetes Service, and the Tailscale Operator automatically removes the device from my tailnet. No stale machines cluttering the admin console and we keep it under the free tier limit as well.

Tailnet access from the sandbox #

Optionally, a sandbox can have access to the 100.64.0.0/10 Tailscale CGNAT range. This allows me to access stuff on my tailnet from the sandbox. I have a few ideas for this, for example deploying netclode from netclode, accessing my Home Assistant API from Netclode, etc.

I needed to switch from Flannel to Cilium to make kube’s NetworkPolicy work properly.

After switching, I had a weird bug with X25519MLKEM768 keys in Tailscale causing TLS handshake failures, so I had to bump my MTU to make it work again 🤨.

I initially wanted to fully block network access from sandboxes, but since the agent service and SDK need to connect to provider APIs (Anthropic, OpenAI, etc.), it would require more work. At least I added a secret proxy so API keys never enter the sandbox. A full air-gapped option could work with local LLMs though!

The agent service #

The agent runs inside the sandbox and handles:

- Git credentials and repository cloning

- Agent SDK initialization and session mapping

- Streaming events from/to the control plane

- Terminal PTY management

- Port exposure requests

It’s written in TypeScript because all the SDKs have (at least) TypeScript bindings. I wish I could do it in Go instead!

The container image #

The agent image is built from Debian Slim. The base layer includes the essentials: git, curl, Docker, iptables, sudo, gh, and mise for on-demand tooling. Then, the SDKs.

The total image is more than 2GB ☹️, because all these bun/node based agents take a lot of space, besides Codex which is in Rust. I tweaked the Dockerfile to reduce the size, but it’s still massive!

Bootstrap sequence #

The entrypoint script does a few things before handing off to the agent:

- Creates

/agent/workspace,/agent/docker, and cache directories, all owned by theagentuser - Starts

dockerdwith VFS storage driver (works on JuiceFS) and data root on JuiceFS at/agent/docker - If a GitHub token is provided, writes it to

/agent/.git-credentials - Creates symlinks from

/agentto pre-warmed caches in/opt(OpenCode installs plugins from NPM on boot… 🫠) - Drops privileges to the

agentuser and starts the Node.js agent

In Netclode, the container starts as root to set up Docker and directories, then drops to user agent (UID 1000) for the actual work. The agent user has membership in the docker group for socket access, and passwordless sudo via /etc/sudoers.d/agent. It’s OK since we’re inside the sandbox.

System prompt and context injection #

The agent injects environment-specific context into the system prompt. The Claude Code SDK is the Claude Agent SDK now, so we need to specify that we want the claude_code system prompt, then I append mine on top. Same for other SDKs.

return {

type: "preset",

preset: "claude_code", // Claude Code's built-in system prompt

append: environmentContext, // My additions

};

The appended context tells the agent about its environment:

You are running inside an isolated sandbox (Kata Container microVM).

- Working directory: /agent/workspace

- Everything persists across sessions: files, Docker images, installed tools

- You have full shell, network, and Docker access

- You have sudo access (passwordless) for system administration tasks

Tools available: Node.js 24, gh CLI, mise for additional versions

Repositories cloned under /agent/workspace:

- owner/repo (primary) -> /agent/workspace

- owner/other -> /agent/workspace/other

This context helps the agent understand it can be more aggressive with installations and system modifications than it would be on a user’s local machine.

Error handling and recovery #

If the agent crashes or disconnects, it restarts and reconnects after a few seconds. The control plane detects the dropped connection and marks the session as “interrupted” if it was mid-task. When the agent comes back, it picks up where it left off. Prompt errors are sent back to the client as error events so the app can display them.

Supporting multiple coding SDKs #

I started with the Claude Agent SDK because I know it’s a good harness. Claude Code is closed-source, and the SDK is as well. I was expecting Claude Code to be a TUI around the SDK, but it’s the opposite! The SDK is the wrapper around the CLI. So I need to install the actual Claude Code CLI in the image as well.

I could have written the agent myself, but that would have been a big project on its own. It wasn’t my goal either: I wanted a good coding agent accessible remotely, nicely. No need to recreate the harness if there are good ones available. This means I get a lot of stuff out of the box: reasoning, sub-agents, TODOs, web search, planning and a well-tuned harness.

The Claude Code x OpenCode debacle #

Then I was curious to support other SDKs, especially after the Claude Code vs OpenCode controversy. Anthropic blocked third-party tools from spoofing Claude Code to use the Pro/Max subscription. It made me want to have the flexibility to swap SDKs.

Netclode currently supports Claude Agent SDK, OpenCode SDK, Copilot SDK, and Codex SDK.

How the SDKs work #

Each SDK has a different communication pattern and interface.

To support all of them, I wrote adapters that implement a common interface:

interface SDKAdapter {

initialize(config: SDKConfig): Promise<void>;

executePrompt(sessionId: string, text: string, config?: PromptConfig): AsyncGenerator<PromptEvent>;

setInterruptSignal(): void;

[..]

}

Each adapter handles initialization, prompt execution, and translates SDK-specific events into a unified PromptEvent format. A factory picks the right adapter based on sdk_type from the session config.

Supported backends #

| SDK | Backends |

|---|---|

| Claude | Anthropic API |

| OpenCode | Anthropic, OpenAI, Mistral, OpenCode Zen, GitHub Copilot |

| Copilot | GitHub Copilot, Anthropic (BYOK) |

| Codex | OpenAI API, ChatGPT subscription |

For OpenCode and Codex, I also support the various reasoning effort levels (low, medium, high, xhigh for Codex; high/max for OpenCode + Anthropic models).

For Codex with ChatGPT Plus, the auth uses OAuth device code flow. I do the auth once with the CLI and store the tokens in a Kubernetes secret to avoid implementing a login flow in the app.

This should probably be a standalone SDK that other people could use to have a ready-to-go adapter!

Secret proxy: API keys never enter the sandbox #

One thing that bothered me: when the agent makes API calls to Anthropic or OpenAI, it needs the API key. But if I inject the key as an environment variable, technically it could be exfiltrated. Even with the microVM isolation, I’d rather not have my keys floating around in untrusted environments.

Inspired by Deno’s placeholder token sandbox feature, I added a proxy system that validates the sandbox identity and injects the API token in the request on the fly. This uses the same ServiceAccount token mechanism as the agent-to-control-plane authentication.

with placeholder key AUTH->>SECRET: add ServiceAccount token SECRET->>CP: validate SA token,

host: api.anthropic.com CP->>K8S: TokenReview K8S-->>CP: valid, pod: sandbox-abc CP->>CP: pod → session → SDK type

→ host allowed? CP-->>SECRET: allowed, use "anthropic" key SECRET->>API: inject real API key (MITM) API-->>SDK: response alt Attack 1: exfiltrate via proxy SDK->>AUTH: evil.com with placeholder AUTH->>SECRET: add ServiceAccount token SECRET->>CP: validate SA token,

host: evil.com CP->>K8S: TokenReview K8S-->>CP: valid, pod: sandbox-abc CP->>CP: host not in allowlist CP--xSECRET: no secret for this host SECRET->>API: pass through unchanged Note over API: evil.com only gets placeholder else Attack 2: bypass proxy SDK->>API: direct to evil.com Note over API: evil.com only gets placeholder end

Here’s how it works:

- The sandbox sees placeholder values:

ANTHROPIC_API_KEY=NETCLODE_PLACEHOLDER_anthropic HTTP_PROXYpoints to a localauth-proxy(inside the sandbox) that adds the Kubernetes ServiceAccount token to requests- The

auth-proxyforwards to an externalsecret-proxyrunning outside the microVM secret-proxyvalidates the token with the control plane, which checks: is this token valid? What session is it? What SDK is this session using? Is the target host allowed for that SDK?- Only then does

secret-proxyreplace the placeholder with the real key and forward to the actual API

Even if someone gets code execution in the sandbox, they only see NETCLODE_PLACEHOLDER_xxx. The real keys are in a separate pod that only injects them for allowed hosts.

The secret-proxy does HTTPS MITM to inspect and modify encrypted traffic, using a CA certificate that’s mounted in the sandbox.

The SwiftUI app #

While the infra and backend parts are very interesting, having a pleasant client is what makes the difference. Who cares about sandboxes and warm pools if the app is a pain to use and full of flickers?

I spent quite a lot of time polishing the app so that it feels nice and legible and smooth. The interaction with the backend being based on a bidirectional stream of events helped make the app feel live and reactive.

I hope, through all the demos I’ve posted so far, that you would appreciate it as well. ☺️

I think animations were one of the things that help it feel pretty smooth with events appearing, view navigation etc. One of my favorite animations is the numericText ContentTransition.

Also, I have to say while Liquid Glass feels terrible on macOS, it really feels so good on iOS, and I tried to use it as much as possible.

The app uses iOS’s @Observable macro for state management. All stores are @MainActor @Observable, and Swift handles the lifecycle automatically. I have separate stores for different concerns: ChatStore for messages and streaming state, SessionStore for session management, TerminalStore for PTY connections, etc. A central MessageRouter routes incoming server messages to the appropriate stores.

Most of the work in the app is handling streaming and rendering tools in a nice way (read, write, edit, bash, etc).

One of the hardest parts was getting event ordering right. Each SDK has different streaming patterns: Claude uses content block indices, OpenCode has pending/running/completed states for tools, Codex returns arrays of events. Events can arrive out of order (thinking blocks may arrive after message content starts), and I need to track correlation IDs to group related events (tool input/output with their tool_start/tool_end). The control plane tracks “logical start times” for events so they sort correctly on reload, not by arrival time. I also need additional logic on the iOS side to make sure the order is right.

Some small touches I like:

- Sessions get auto-named after the first prompt. The agent sends the prompt to Claude Haiku which generates a short title.

- An auto-paused session is resumed when the user taps the input bar, to save a few seconds

- All the reconnecting and offline logic to make the real-time experience feel seamless and resilient.

What I didn’t like, building this app, is the dev workflow. The Xcode build times are so slow… And we don’t get hot reload like on web, or web-based tech.

Connection resilience #

Handling persistent connections on mobile is not easy because lots of things can happen. Especially when losing connection, switching from 5G to WiFi, sleeping, or multitasking.

I also had issues with URLSession’s HTTP/2 implementation, somehow it has compatibility issues with Tailscale’s iOS network extension. On my physical iPhone, bidirectional streams would drop after 10-15 seconds, but not in the simulator (Tailscale is on my Mac, not in the simulated iPhone).

I ended up using NIOHTTPClient instead of URLSession.

The tricky part was handling network interface changes. When you switch from WiFi to cellular (or vice versa), the old connection might still look “connected” to the OS but is actually dead. I added a NetworkMonitor using NWPathMonitor that detects interface changes and proactively triggers reconnection before the user notices anything. For background/foreground, SwiftUI’s scenePhase does the job.

There’s also a keep-alive mechanism: if no activity for 30 seconds, the client sends a .sync message to validate the connection is still alive. This catches dead connections early instead of waiting for a timeout. And since Redis Streams persist all events with unique IDs, reconnecting clients just send their last seen ID and pick up where they left off.

Here is an attempt at a state diagram representing the possible scenarios. There’s quite a few!

For multitasking, when the app goes to background, I close the connection gracefully to save battery. The last seen stream ID is persisted to disk. When the app comes back to foreground, it reconnects and picks up from that cursor. If you send a message while offline, it gets queued locally and replayed automatically when the connection is restored.

Streaming markdown #

For markdown rendering, I use MarkdownUI with custom theming. For code blocks, I have a custom CodeBlockView with syntax highlighting (via Highlightr). MarkdownUI handles incremental updates reasonably well out of the box. Agent responses come in chunks with partial: true flags. Each chunk gets accumulated in the store, and SwiftUI re-renders the markdown view.

Voice input #

I love the ChatGPT voice prompt feature. Whisper is so good compared to the iOS native keyboard dictation, it’s very handy for long prompts. I wanted to add it to the app. I settled for iOS 26’s new SpeechAnalyzer framework, which is on device and works very well!

The first time you use it for a given language, the app downloads the ML model (about 50MB per locale). After that, transcription is very fast and runs locally. I use the SpeechTranscriber for real-time streaming of the transcribed text. And also a little waveform visualization 😬.

iOS and macOS #

I started with a web app and iOS, but realized I was building mostly for on-the-go prompting. So I scrapped the web app to avoid having to double-implement everything and keep my focus. For desktop, the app works as a Mac Catalyst app!

The layout adapts based on size class:

- iPhone:

NavigationStackwith a sessions list - iPad/Mac:

NavigationSplitViewwith a sidebar

The app isn’t as nice as a native macOS app would be. I think an option is to actually make a separate native macOS app and make the codebase modular to share as much of the code as possible between iOS and macOS, but it’s a bit more work.

But it’s nice to be able to start or continue a session on desktop.

Git diff view #

The app has a built-in diff viewer to see what the agent changed. The agent runs git status --porcelain to list changed files with their status (modified, added, deleted, untracked), and git diff --numstat to get line counts. When you tap a file, it fetches the full diff. For untracked files (which git diff doesn’t handle), the agent generates a synthetic unified diff showing all lines as additions.

On the iOS side, I parse the unified diff format into files, hunks, and lines. Each file section is collapsible.

The interesting part is word-level highlighting. Git can do --word-diff, but I’m using standard unified diffs which are line-based. So when I see a deletion followed by an addition (a modified line), I tokenize both lines into words and whitespace, then diff them using Swift’s built-in difference(from:) algorithm. This gives me exact character ranges that changed, which I highlight with a stronger background color on top of the line-level red/green.

On top of that, I apply syntax highlighting based on the file extension, so I get both proper code colors and word-level change indicators.

Live terminal #

This is a cool feature: live terminal access on the sandbox. It was easier to implement than I expected. On the agent side, I spawn a PTY with node-pty and stream the I/O through the Connect RPC connection. On the iOS side, SwiftTerm does the heavy lifting for terminal emulation.

It’s a full terminal emulator! SwiftTerm is really nice, and the keyboard overlay with the common keys that we use on desktop is amazing!

It works really well. You can run htop, vim, or even Claude Code itself inside the terminal… because why not!

This is a pretty cool feature that I don’t expect will ever make it to commercial cloud coding agents. It’s nice to be able to debug a session, run commands myself, install tools, etc.

CLI shell access #

The iOS terminal is great on the go, but sometimes I’m at my computer and just want to SSH into a sandbox. So I added a netclode shell command to the Go CLI that does exactly that. The UX is similar to sprite console from Fly.io’s Sprites, which also gives you interactive shell access to sandbox VMs.

# Create a new sandbox and drop into a shell

netclode shell

# With options

netclode shell --name "dev box" --repo owner/repo --tailnet

# Attach to an existing session

netclode shell <session-id>

It puts the local terminal into raw mode and forwards all I/O through the same Connect RPC bidirectional stream as the iOS app. So you get full interactivity: colors, tab completion, vim, htop, everything. Ctrl+] detaches without stopping the session (you can reattach later), and Ctrl+D or exit exits normally.

One fun implementation detail: detecting when the remote shell exits. The problem is that the CLI has no direct way to know, it only sees a stream of terminal output bytes forwarded through the control plane. So I used an OSC (Operating System Command) escape sequence as a signaling mechanism. OSC sequences are part of the terminal escape spec and follow the pattern ESC ] <code> ; <payload> BEL. Terminals use them for things like setting the window title (OSC 2) or clipboard access (OSC 52). The nice thing is that terminals are required to silently ignore OSC codes they don’t recognize.

So when the PTY process exits inside the agent, it emits a private OSC with a made-up code (\x1b]9999;pty-exit;<exitCode>\x07) into the terminal output stream. The CLI’s receive loop scans each chunk for this marker, strips it from the output, and triggers a clean detach. The iOS app’s SwiftTerm terminal just ignores it, since 9999 is not a recognized OSC code. It’s basically an in-band signaling channel hidden inside the terminal stream, which is a neat trick to avoid adding a separate control channel for this.

Local inference #

At some point I moved my Netclode host to be on my gaming PC, I had to try to use the GPU a bit.

I was thinking of doing GPU PCI passthrough to the sandboxes first, a bit like my Plex setup, but that would tie the GPU to a single sandbox at a time. Instead, I run Ollama as a shared service that all agents can access, meaning I can have multiple sessions at once using local inference. If they don’t use the same model, it needs to be reloaded though.

NVIDIA GPU Operator #

Getting my RTX 5080 working in Kubernetes required a few layers:

- On the host: NVIDIA drivers + kernel modules

- For containers: NVIDIA Container Toolkit (hooks into containerd to mount GPU devices into containers)

- On Kubernetes: the device plugin (exposes

nvidia.com/gpuas a schedulable resource)

The NVIDIA GPU Operator can manage all of this, but it’s designed for cloud environments where you want everything automated. On my single-node setup, I pre-installed the drivers on the host and configure containerd manually in my k3s setup. Two reasons: the operator’s driver containers only support Ubuntu and RHEL (I run Debian), and I have Secure Boot enabled which requires DKMS signing. So I disable most GPU Operator components and only use it for the device plugin:

driver:

enabled: false # Pre-installed on host via apt

toolkit:

enabled: false # Configured in k3s containerd config

validator:

enabled: false # Fails with pre-installed drivers

devicePlugin:

enabled: true # Exposes nvidia.com/gpu resource

nfd:

enabled: true # Node Feature Discovery, labels nodes with GPU info

Once the device plugin is running, pods can request GPUs. In my case, only Ollama needs it:

resources:

limits:

nvidia.com/gpu: 1

nodeSelector:

nvidia.com/gpu.present: "true"

Ollama setup #

Ollama runs as a regular (non-Kata) pod with GPU access. I use OpenCode as the SDK since it has built-in Ollama support via the ollama/ model prefix.

I only tweaked a few Ollama seetings. The context length, which stayed at 4096 by default, like in the good old days, and two things to save some VRAM, seems I’m struggling even with 16 GB: Flash Attention and reducing the quantization type for the K/V cache.

env:

- name: OLLAMA_KEEP_ALIVE

value: "24h" # Keep models loaded in VRAM

- name: OLLAMA_FLASH_ATTENTION

value: "1"

- name: OLLAMA_CONTEXT_LENGTH

value: "32768" # default: 4k

- name: OLLAMA_KV_CACHE_TYPE

value: "q8_0" # default: f16

Working models #

With 16GB VRAM (RTX 5080), I tried these models:

devstral-small-2:24bMistral’s new coding model, OK tool calls, but gave up easilyqwen3-coder:30bSame as devstral basicallyqwen2.5-coder:14bunable to do reliable tool calls

Overall, not great, but I don’t think the issue is with models themselves, with this short context size, the tool calling becomes really hit or miss, models don’t pass the correct format to the harness. Or they just give up too easily. OpenCode is not the most optimized harness for such small models (there is a lot of open issues around Ollama support). So in reality, it’s not a very usable setup with my GPU. But in a year or two, it will be I think!

I went with Ollama over vLLM because it’s simpler to set up and has good OpenAI-compatible API support out of the box. I read that vLLM would give better throughput for multiple concurrent requests, but I’m the only user anyway.

Running it yourself #

As I said, this is self-hostable! Even though the stack might look a bit complex, I tried to make it super easy to setup, ideally in a single playbook run.

You need:

- A Linux server with KVM and nested virtualization support (Hetzner cloud doesn’t!)

- A few env variables (S3 credentials, GitHub API keys, at least one provider API key, etc)

- Tailscale

You run the Ansible playbook and everything gets deployed: k3s, Kata, JuiceFS, the control plane. Then just open the iOS app and it works!

I started with an OVH VPS, which has pretty damn good performance, since Hetzner is not compatible. Home server works too if you have Tailscale set up. I repurposed my gaming PC’s second SSD to Debian 13 and use it as my Netclode host now:

For iOS, I didn’t publish the app to the App Store, but you can build it yourself and input your control plane URL.

What’s next? #

- iOS push notifications when a session finishes (but I need to pay Apple)

- Leverage JuiceFS and copy-on-write to fork sessions with the entire context

- A proper TUI maybe? And web app?

- Support MCPs, Skills

- Custom environments (with variables, secrets)

- Offline sandboxes

OK, that was a big one #

This was a really fun project that combined a lot of things I enjoy: backend, infra, mobile, and good UX! (or well, I tried…). I realize now this post is quite massive!

If I had to build it again, I might do my own orchestrator and skip k8s, because that’s part of the fun! I might even go for a lighter weight sandboxing mechanism such as Boxlite.

The cloud coding agents will probably keep getting better, but at least I have options now, not tied to any of them. 😄 And I can add pretty much any feature I want, thanks to the agent itself.

The code is at github.com/angristan/netclode. Enjoy!